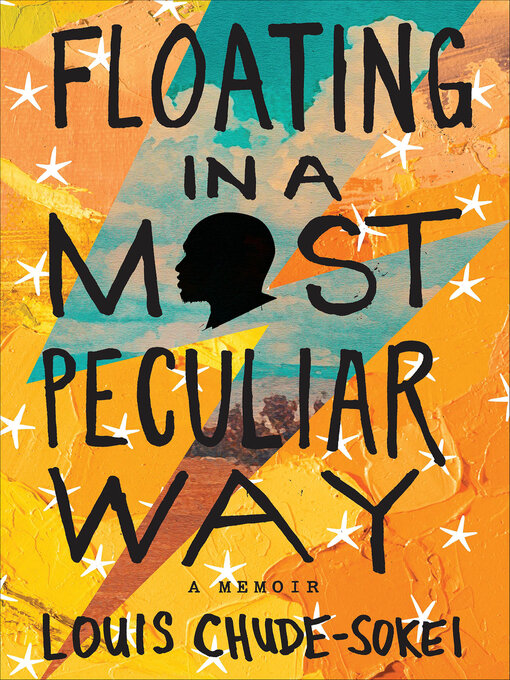

The astonishing journey of a bright, utterly displaced boy, from the short-lived African nation of Biafra, to Jamaica, to the harshest streets of Los Angeles—a searing memoir that adds fascinating depth to the coming-to-America story

The first time Chude-Sokei realizes that he is “first son of the first son” of a renowned leader of the bygone African nation is in Uncle Daddy and Big Auntie’s strict religious household in Jamaica, where he lives with other abandoned children. A visiting African has just fallen to his knees to shake him by the shoulders: “Is this the boy? Is this him?”

Chude-Sokei’s immersion in the politics of race and belonging across the landscape of the African diaspora takes a turn when his traumatized mother, who has her own extraordinary history as the onetime “Jackie O of Biafra,” finally sends for him to come live with her. In Inglewood, Los Angeles, on the eve of gangsta rap and the LA riots, it’s as if he’s fallen to Earth. In this world, anything alien—definitely Chude-Sokei’s secret obsession with science fiction and David Bowie—is a danger, and his yearning to become a Black American gets deeply, sometimes absurdly, complicated. Ultimately, it is a boisterous pan-African family of honorary aunts, uncles, and cousins that becomes his secret society, teaching him the redemptive skill of navigating not just Blackness, but Blacknesses, in his America.